I’d been in Fez two days when Uri, a gal from my hostel, unfolded a map on the breakfast table and invited me to join her tour group for the day. I balked.

I don’t like formal tours—the sight-seeing, tight schedules, and gift shops leave me feeling flat. Plus, I had my stereotypes: Uri was from Thailand and her friends were from Indonesia and Korea. In my experience, Asian tour groups spend a lot of time taking snaps. And they probably had jobs in tech and would want to talk computers.

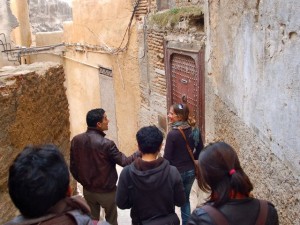

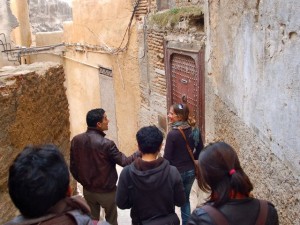

But by the time we finished our eggs and coffee, I was convinced. If we pooled our money, the tour would be cheap. Plus, the last couple days in the medina left me feeling like a walking wallet. Grouping up afforded protection from the aggressive street touts in the way that schooling protects fish from sharks. It’d be easier to get around.

Our first stop was a museum. Uri and I walked down a freezing cold hallway lined with glass-encased heirlooms: an old sundial, some rusty earrings, tattered rugs. But both of us were more interested in the living than the dead inert objects of the past. We found our way outside again.

We strolled between rows of mint and orange trees, and talked about Thailand. I was there last year. My recollections were largely culinary: the crunchy streetcart Tom Sum, the ubiquitous phad Thai, the milky-sweet iced-teas that were my afternoon ritual. And, of course, it’s impossible to not remember the prostitution–the absurd upside-down universe where old-pot-bellied “Sexpats” strolled the streets with young tottering Thai women.

What’s the deal? I asked her. Is this really just “part of the culture” as I’d always heard (often from the Sex-pats themselves)

She flinched. Started to speak and stopped. A flash of adrenaline stuck her for words. The issue seemed close to the surface, and I felt bad for bringing it up.

”This is just the tiniest portion of the population,” she seethed, “but everyone thinks that all Thai women are easy sex.” Once, a guy sitting next to her at a conference turned to her and declared they would be having sex. And she is wary of English teachers in Thailand, unsure if they are viewing her in sexual terms.

There are many versions of Thailand, but in her version, prostitution is frowned upon and getting together with a foreign guy is questioned. But she added a caveat: sometimes real love blooms, and isn’t given proper credibility. A friend of hers is in a legitimate relationship with an American and struggles with the disrespectful assumptions people make about their relationship. Everyone is sure she is just after his money.

“Is this really what outsiders think of us–that we are just sex?” she asked.

I had to admit that sometimes it seemed that way. Not a week went by on Facebook without someone announcing they were going to Thailand followed by a chorus of comments: “Don’t forget the condoms!” or “Have fun. Wink-wink.” And, even my own travels there left a strong impression: I’ll never forget the Twilight Zone that was Pattaya: an entire boardwalk lined with girls and old men—some even shuffling walkers—trolling for evening company. Admittedly, this was a huge tourist area.

“But people think of a lot of other things too,” I countered. “Great beaches, kind people, gilded temples.”

After the museum, our group moved on to a café. As we sipped our mint tea, our discussion of stereotypes broadened to include the rest of our group: two were Muslims from Indonesia, and the other from South Korea. I mentioned that I’d just finished reading Ayann Hiri Ali’s book, Nomad, which although reflective of Ali’s own experience, seemed to fan many of the West’s greatest fears about Muslims: the oppression of women, forced marriages, genital mutilation, extremism.

Bowo shook is head. These stereotypes did not fit the Muslims he knew in Indonesia.

Noka was also Indonesian and had studied in The States—in a small Pennsylvania town. He said that sometimes people asked him if he had a television. Or, worse, if he lived in trees. One person asked if he drove to the U.S. from Indonesia.

“What is the stereotype of Americans?” I asked.

“Ignorant,” he said. We all laughed. Though the stories about American naiveté often seemed exaggerated, it might have been the truest stereotype at all.

Afterall, I just had to consider the stereotypes I’d started the morning with: that we would spend the dull day posing for photos and talking about computer programming. Instead, we experienced what travel does best, which is rattle the rust off our world view that accumulates when we stay in one place for too long. That morning we’d left the hotel as a Thai Prostitute, a Suicide Bomber, a Primitive, a Techie, and a Moneyed Ignoramus, and returned as real people with real names: Uri, Noka, Bowo, Hyo and Christina.

Rounding the bend into Tarifa, I had to revise my expectations. I’d presumed the beach town, located at the southernmost point of Spain, was a winter-escape from northern Europe. My bikini and SPF waited at the top of my bag, and I was ready to toast the sunshine with a mojito.

Rounding the bend into Tarifa, I had to revise my expectations. I’d presumed the beach town, located at the southernmost point of Spain, was a winter-escape from northern Europe. My bikini and SPF waited at the top of my bag, and I was ready to toast the sunshine with a mojito.